An Irish Perspective

May 31st 2012 is a date likely to resonate with generations of this country for years to come. That day the people of Ireland will be asked to either support or reject the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union, or the Fiscal Compact to you and I. Unfortunately the day is fast approaching, and with 19% of the population undecided as to which way to cast their vote time is running out. The American writer Henry Adams' assertion that "during a campaign the air is full of speeches- and vice versa" has never seemed so apt. This campaign, like most others in this country, has been dogged by a litany of mistruths, political point scoring, and claim and counter-claim . To distinguish fact from fiction has been an unnecessarily arduous task. The following seeks to chart a different course and lay out the facts of the Treaty as they pertain to its key elements.

Firstly it is important to establish the budgetary changes that the Fiscal Compact will initiate if ratified. The Compact;

- introduces a lower limit of a structural deficit of 0.5% of GDP

- requires member states whose Debt:GDP ratio is greater than 60% to reduce this ratio at an average rate of 1/20th of the deviation per annum. (i.e. if a country's Debt:GDP ratio is 80%, then the deviation from the threshold is 20% thus requiring a reduction of 1% per annum.)

- introduces the key provision that budgetary rules shall be enshrined in national law through provisions of "binding force and permanent character, preferably constitutional." (Article 3(2) )

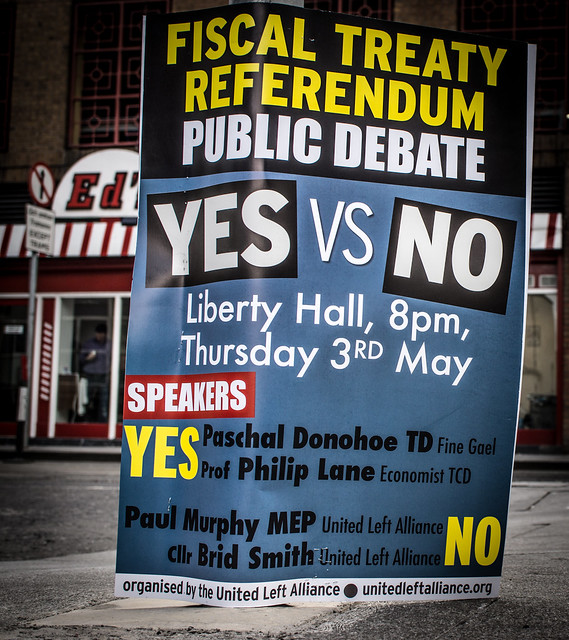

It is prudent to note that the Fiscal Compact itself does not alter much by way of budgetary provisions as set under the 'six pack' of reforms introduced in late 2011. The key innovation is the proposal to enshrine these provisions in national law. Philip Lane, Professor at TCD notes that "domestic legal requirements are more likely to induce fiscal discipline than external rules such as the SGP, since only the domestic system can effectively hold a government to account". Given the weak fiscal governance and enforcement that checkers the history of the EU Council, Prof. Lane might just have a point.

Bunreacht na hÉireann

If ratified the Treaty will introduce a new way of measuring budget balances- the structural deficit. The introduction of the structural deficit has caused consternation amongst some commentators, but drawn high praise from others. Essentially, the structural budget makes sense. It takes into account changes in the business cycle and may therefore aid governments in implementing sustainable fiscal policies and effectively promoting macroeconomic stability through counter-cyclical measures. The problem is the structural deficit is not easily calculated, in fact no consensus exisits as to whether it can be accurately calculated at all. It seems wholly illogical and irresponsible to base facets of such an important treaty on a concept which is incapable of meaningful measurement. Brian Lucey, Professor of Finance at TCD perhaps then put it best in stating that"we are asked to support the immeasurable in the pursuit of the unattainable." Regrettably it appears support of the structural deficit is a matter of faith and no more.

Another topic of debate in this referendum is the access to funding that the State will have as a result of the vote. In reality, however, little time and effort need be exerted in the discussion of this issue. Should we reject the Treaty, Ireland will not have access to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Only those member states that ratify the Treaty will have access to these funds. Consequently, were the country to need a second bailout (as is looking increasingly likely) it is unclear as to where the money would come from. Rejecting the Treaty sets our course through uncharted waters in this regard. Alternative sources of capital have been mooted, such as simply raising funds through the market or receiving further assistance from the IMF. It seems unlikely, however, that the IMF would provide such funds, or at the very least wholly speculative that they would do so. Minister Michael Noonan has also advised the Dáil that the IMF has "indicated that it will provide funding to Ireland only as part of a European initiative". Even more unlikely is the prospect of reentering the bond markets in late 2013 at any reasonable interest rate. As recently as Wednesday (23rd May) the National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA) advised that rejection of the Treaty "would mean in all likelihood that it would not be possible for Ireland to re-enter the bond markets at sustainable rates".

The final bone of contention for many is the proposed introduction of a Financial Transactions Tax (FTT). Bear in mind, The Fiscal Treaty does NOT expressly include these proposals, instead it is thought that ratifying the Treaty would lead inevitably to greater fiscal unity and integration which would ease the way for the introduction of such a tax. The tax, commonly referred to as a 'Tobin tax' would apply to the sale and purchase of financial instruments, when transfer of ownership occurs, a levy must be paid. The concept is no different to say the working of a property tax. There are too schools of thought on the issue. The first, argues in the name of prudence and equity that it is high time such a tax were introduced as it would serve to curtail the highly speculative trading that initially led to the financial crisis and would also force the financial sector to contribute towards the resolution of a problem they helped create. Conversely, the Irish government is staunchly opposed to such a tax and perhaps with good reason. It is their belief that the imposition of such a tax would be catastrophic for the financial services sector in this country, in encouraging business to migrate to non-taxable areas. David Cameron has already vowed to fight the tax in defence of the City of London and refused to back the Treaty at a summit late last year as a result. The fear is that those in the IFSC will follow the path trodden by the Irish diaspora of times both past and present, in heading for the safe refuge and greener pastures of the city of London.

Dublin's International Financial Services Sector (IFSC)

Ratifying this Treaty guarantees the country access to future funding in the all too likely event of needing to access it. It seeks to encourage a degree of fiscal discipline which has been largely found wanting in the history of the State, and as such must be welcomed. Unfortunately it is likely to send the country into further decline and deeper recession, along with the other fringe nations of Europe. It is flawed in the absence of any growth agenda and seeks to impose sanctions on offending nations in the name of a concept many experts consider immeasurable. It may help herald the introduction of a tax regime whose costs and benefits have not been adequately determined and enshrines budgetary provisions in national law. The war currently being waged for the favour of the people is a tumultuous affair. One that cares for its outcome is faced with any number of conflicting views, through which they must sift in order to cast their vote with conviction rather than faith.

The edict handed down by the will of the German's is a tough pill to swallow, yet perversely it might be in the country's interests to do so given the forsaken state we find ourselves in and the prospect of even greater hardship that lies ahead should we decide not to.

No comments:

Post a Comment